|

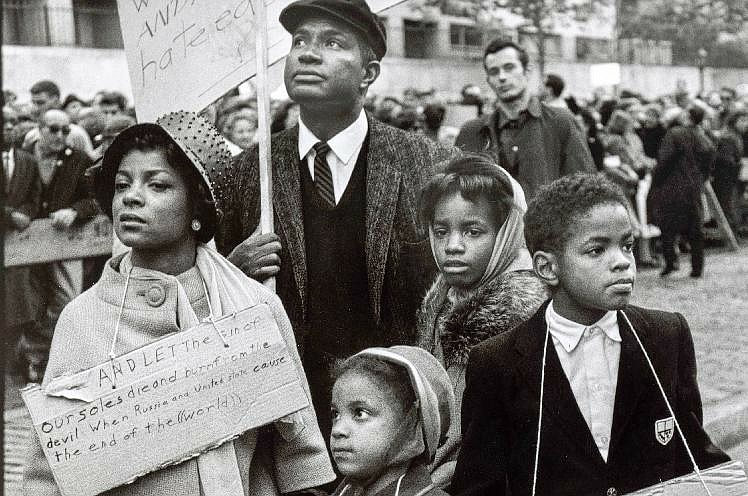

As nine o’clock neared and the nerves I’d thought were subtle jitters failed to subside, I couldn’t help but wonder how my interviewee, Dr. Hasna Muhammad, is preparing for our quick chat, miles away in New York. After I’d confirmed our interview time and day weeks before, I did a lot of wondering about what kind of woman she might be- how she’d sound, if she’d be kind, and how deep she’d allow our conversation to go. Among the women I had the It’s nine o’clock now and I hesitantly begin to to dial her number. After the phone rings twice, I hear a “hello?” on the other side that sounds comfortably familiar, like a relative I haven’t spoken to in a while. And although we’ve had short conversations via email regarding one another’s schedule and the general purpose of the interview, I tell her a bit about myself, stumbling over words here to there. Dr. Muhammad is intrigued by some of the things I mention to her like my major, and where I go to school, Howard University, which we discuss her connection with in length later on. Before we get there, I begin with a question about her decision to pursue art and activism, as both of her parents did during their time. “It really wasn’t an overt realization. Activism has been an innate part of our family life since I can remember. Even when I was in a stroller, I’m told my mother [actress and civil rights activist, Ruby Dee] and her associates would take us to march for jobs. There’s a famous photo of us protesting, so it’s never been far from what I normally did as a child and member of the family, and that goes for my brother and my sister as well.” “There was a time, though, that I did make a decision to become an artist, but it came in iterations. The first was when our parents would talk to us around the dining room table about the state of the world, and Black people specifically, and they wanted to know what we thought about things like poverty, or what we were going to do about the lack of African Americans, especially women, behind the scenes of artistic endeavors - writers, directors, producers, cinematographers. I remember we had a conversation in the kitchen about the need for African American folks behind the scenes, and it sparked in me a desire to write, to be a visual storyteller, and it all came very naturally after that.” Next, I asked her to consider the state of our world today, and, from one Black artist to another, what kind of content she’d like to see Black artists create. Her answer was simple. “I’m always pleased when the works of Black artists are published, because that hasn’t always been the case. The type of work that I pay attention to is the work that elevates us as a people, helps us increase knowledge of our history, helps social justice initiatives, fights for self-preservation and improvement. I do know there are works that may not purposefully intend to elevate us specifically, but I like it when I see it. I also like it when it’s just good work, plain good work, and the artist is African American. When it transcends any narrative and just is good, oh.. I love it!" Maybe foolishly, I had to ask her which piece of artwork that she’d made thus far made her the most proud. And as I expected, she told me it’s yet to be created. “I’m always striving to be able to articulate more clearly, more sustictly, and more broadly my interpretation, my take on my environment, and I just haven’t done it yet. I believe that the short short about the killing of Kenneth Chamberlain would be something that I could say I’m very proud of. Kenneth Chamberlain was a 68 year old retired marine who, in November of 2011, was shot and killed with a police officer in his own home. His life alert was activated accidentally and they responded, and about an hour later, he was killed. That is definitely one of the things I am most proud of, and there’s more to come.” About that “more to come”, she didn’t say much but she did give me the scope of the project. “I have been doing a lot of photography, taking a lot of photos in central Harlem. I think my next project will come about as a result of the various initiatives that I’ve been drawn to. One specific initiative is about an organization that is helping to prepare entrepreneurs be able to become successful business owners in Harlem. There are always stories about the gentrification in Harlem and the face of Harlem is changing as you and I speak, but that doesn’t mean that the current community can’t be apart of or maintain its voice and integrity within that process. That’s all that I’m prepared to say-there’s a little bit more than that, but I think that’s all I want to share right now.” After my questions had been answered, the two of us spoke about the scholarship the existed in her father’s name at Howard University and his connection to the school that he attended for a short period of time. I learned that the school of communications-my school, SOC gang!-held an important place in the heart of her family, due to the love her father had felt their during his matriculation. We also discussed my connection with the internship that brought us together and how I formulated the questions that I’d asked her. I shared with her that I had been interviewing young Black creatives during my time at the Dinner Table Documentary, and that she, in essence, was what the girl’s that I’d spoken with and I ultimately aimed to become one day. Through this conversation, I realized that although this was the first time we’d spoken, our similarities and our mutual love of art and people are likely why she’d felt so familiar to me in the first place. I also better understood a crucial component of what it means to reach out to those who’ve come before you and why it’s important-in less than thirty minutes, I’d felt like I’d found a living goal to strive towards. Written by Iyana Botts

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed