|

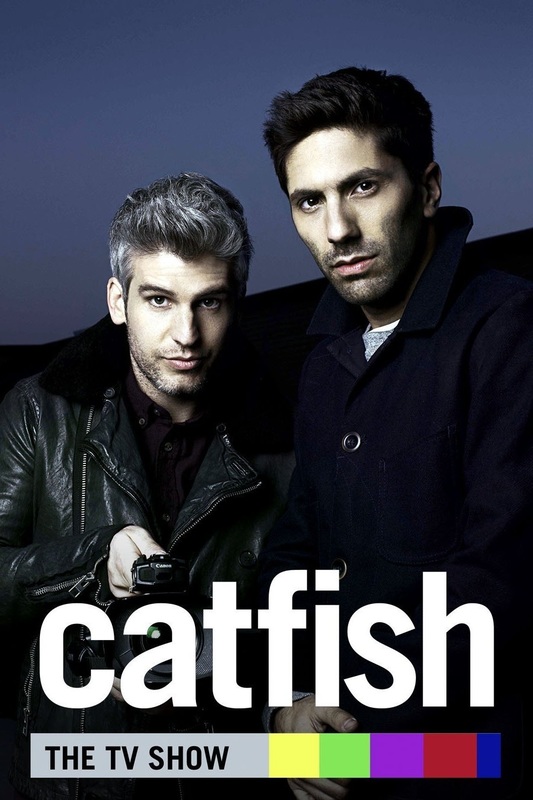

Reality TV is second behind Bollywood films as my favourite form of entertainment and there’s a commonality between them. Bollywood films exist as a combination of reality and fantasy, with characters who seem to live in our world suddenly breaking into song and dance at the slightest occurrence (often featuring cliffs and wind), and therein lies the similarity between reality TV and mainstream Bollywood. Reality TV is the scene where the cast break into song and dance with outfits to fit the part, but this time the producers are trying to convince us that it happened naturally. They put on their outfits for their part, like the ‘angry black woman’ or ‘sassy gay man’ and start the show. Seeing people act out scenarios that are so ridiculous you’d think they were fictional (and lets be honest, they probably are) is somehow more interesting, more exciting and more immersive than watching something that’s ‘made up’. Because of this reality TV is also a medium where groups that are often underrepresented in the media, like Black women and the LGBT community, can sometimes take precedence, for better or worse. [Editors Note: This article was originally published in 2015-- all show descriptions refer to previous seasons and episodes.] Before I go any further I’d like to say that this was inspired by some tweets by @Kahduna in which she mentioned how shows like BGC perpetuate negative stereotypes about black women but don’t shape the image of white women in society, as they are represented in a variety of ways through the media. In Oxygen’s ‘Bad Girls Club’ a group of self-confessed ‘bad girls’, or women with severe anger issues, are thrown together in a house and the producers wait for them to fight. That’s the entire premise, and they all fall for it every time. 14 times now, in fact. Without failure these women who for the most part have never met each other will have fought at least once before the end of the 3rd episode. Alliances are made, punches are thrown, and most pathetically of all, grown women go around scribbling on photos of each other to express their dislike for one another. It is important to note that this show is one of few that have a number of black women on the cast, with 4 out of 7 of this seasons girls being black. Photos of 2012, 2014 and 2016 Cast Courtesy of Oxygen.com However, this representation is far more damaging than it is helpful. It may as well be giving those who believe in the ‘angry black woman’ stereotype a pat on the back and a thumbs up for being right. This show says ‘You were right, and here is the evidence to prove it’. And it only takes a quick sweep through the Youtube comments to prove it. Comments like ‘I hate angry black bitches’ are prevalent. The hate towards black girls is pointed and personal, with the footage used as evidence for generalisations. The fights are often childish on both sides but the black girls get all the flack. But sometimes they are justified. For example Jayla’s disagreement with Lauren. Jayla told Lauren that she cannot and should not use the N word and is being painted by many as the villain, whilst Lauren is encouraging one of her housemates to cheat on their partner on national TV for her own entertainment and is a foolish but harmless county bumpkin. Lauren spends the majority of the show drunk and yet her appearance on the show won’t be used to bolster negative stereotypes about white women, because for every Lauren there are tens of thousands of Rory Gilmores whilst black women being are always the same: violent, ignorant or plain repulsive. It is clear that whilst tension does exist in the house, the black members of the cast are not as ignorant as they appear to be. The producers clearly manufacture scenarios to cause tension (anyone for a cigarette?), therefore, even the behaviour of these women cannot necessarily be viewed as representative of themselves. The environment they are in is designed to break people and cause them to act out, and yet their behaviour is used to generalise an entire group of people, but that’s another article for another day. Another thing that is painfully clear is that many of these women have underlying mental health issues which are exploited for comedic effect and drama. The producers of BGC have been addressing this issue in the most fake and transparent way possible, by bringing in a counsellor that encourages the women to delve into their deeply held emotional issues on camera for the pleasure of the viewers. The producers of MTV’s Catfish are a little more ruthless, and they don’t have time for the guise of caring about the people on the show, and let them lay it all out with the help of pseudo-counsellor Nev.

The Catfish in these episodes is almost always a butch lesbian. They’re portrayed similarly to the girls of BGC: unattractive, aggressive and most importantly, repulsive. In the episodes where the girl knows she is in a lesbian relationship she is pretty much always feminine. She is usually expecting to meet another ‘pretty’ (but not necessarily super femme) girl and is confronted with a fat butch lesbian. A recipe for success, obviously. The Catfish in question is greeted with distaste from the victim. I feel like often this stems more from the fact that they find the person who Catfished them unattractive and a sense of shock at their appearance as opposed to anger or sadness. The Catfish is often rather cruel (‘David’ aka Christina leads on a girl for 10 years and then tells her she never loved her) or close to psychotic (Sydney from season 4 who creates over 10 profiles to stalk her girlfriend with). The message is loud and clear: ‘pretty lesbians are okay, but butch lesbians are crazy fat and evil.’ Media representation for marginalised groups can be a double edged sword. As thrilling as it may be to see a black or LGBTQ or disabled person that mirrors what you are – at least in the most superficial of senses – this representation can often be negative, intended to entertain the audience that already hold these stereotypes by giving them a feeling of vindication in the idea that all people from this group are the same. This is dangerous as it increases the marginalisation and dehumanisation of these people until they become mere tropes, the focus of jokes or aggression, and not individual human beings who deserve respect.  Written By: Becky Olaniyi, a 19-year-old student from London who speaks on being young, black and disabled-- discussing and dismantilyn the social issues around disability

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed